In part one of our series, our overview of Building an incident response plan, we discussed what regulations organizations will need to meet in order to address incident/breach response protocols laid out in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This week, we’ll talk to you about steps to take to actually create your company’s incident response program.

An incident response (IR) plan does not need to be overly complicated or require reams and reams of policy, standard, and other documentation. However, having a solid and tested framework for the program is key in the ability of an organization to respond to and survive a security incident.

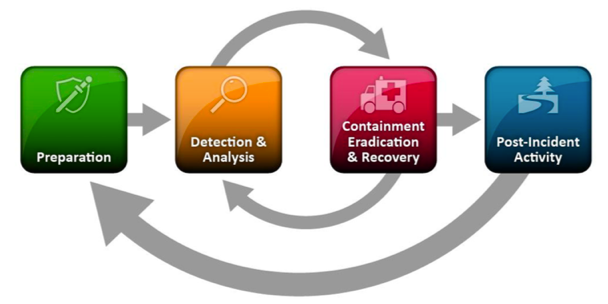

There are many different incident response frameworks from security companies and organizations that are useful in their own ways. From my experience, the simplest, yet most robust framework to build upon is the US government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Procedure (SP) 800-61.

There are four key steps within this framework: preparation, detection and analysis, containment eradication and recovery, and post-incident activity.

Preparation

In my opinion, preparation is probably the most important step in incident response. An organization that is not prepared to handle an incident will almost always fail to appropriately detect, let alone respond to, a security incident. Preparation, of course, includes establishing an incident response program, including all the necessary compliance and governance documentation (including policy, standard, and procedures, at a minimum). More on this later. But it also includes socializing the different aspects of this program so that it can be effectively executed. That includes the following steps:- Maintain a 24x7x365 call-tree for all departments within the organization.

- Design (or procure) and implement security monitoring equipment.

- Outfit incident response staff with the appropriate equipment, software, access, chain of custody forms, secure storage locations, and war rooms.

- Educate staff and incident responders with what is “normal” within the environment—installed software, permitted ports and protocols, acceptable use policies, etc.

- Create a central email address for security or incident response, and provide access to the mailbox to appropriate personnel. This should be a shared mailbox vs. a distribution list to allow for better archiving and searching.

- Provide continuous training for staff through internal and external training sessions.

- Test the incident response process and detection/response tools regularly through realistic scenarios and mock indicators.

Detection and analysis

In addition to staff being notified of security events via automated alerting (email, SMS, etc.), staff should perform threat hunting activities and review security tool administrative interfaces. They can do so through the following processes:- Identify any abnormal activities through security tool monitoring and reviewing.

- Monitor central email addresses for reports of abnormal or malicious activities.

- When an alert or report indicates a security event:

- Review the alert or report for accuracy and validity.

- Utilize a security information and event management (SIEM) system to correlate event indicators against other logs and tools.

- Investigate indicators against public information such as WHOIS, DNS, threat intelligence sources, and other resources to identify information about the potential attackers.

- Maintain a report of the activities performed, timeline, and outstanding actions—this should be a formal report for more severe or in-depth incidents.

- Prioritize the incident among other organization and security activities (impact of data loss, downtime, recovery time, etc.).

- Develop steps for communicating the status of an incident to internal management and staff, as well as customers or external partners.

Contain, eradicate, and recover

- Consider the containment strategy: Should you wipe and rebuild or can the organization support monitoring the malicious actors for a period of time to ensure all impacted systems are known?

- Ensure all evidence is gathered in an approved, secure, and structured manner and is stored in a secure location to prevent tampering or loss.

- If desired, attempt to identify the attacking host.

- Remove malicious software or rebuild hosts to a known clean state.

- Notify impacted customers or regulatory agencies within 72 hours or as required by contracts or regulations (including GDPR).

Post-incident activities

Once the breach has been secured, computers restored, and impacted customers notified, there’s one last stage to consider. Evaluating what happened after the fact can ensure a smoother response in case of future attacks.- Gather all responders (from within security and from other teams) to discuss how the incident was handled and ways to improve response in the future.

- Utilize indicators from the incident to update security monitoring tools.

- Notify external entities related to the indicators discovered; for example, the domain owner for a website that was compromised and delivering malicious content.

- Update incident metrics and key performance indicators.

- Retain the evidence for a prescribed timeframe—pay attention to the potential for future legal actions when considering retention times.

Policy, standards, procedures, and guidelines

I am the last person to push compliance or governance over technical action, as I have seen and created too many policy documents that just sit on shelves. However, I do feel incident response is one place where having solid governance and documentation is critical.Policy

An incident response policy document should establish the IR program and team structure and, probably most importantly, emphasize ownership and buy-in for the IR program at the executive level. This document will provide the highest level of requirements for the program—the key policy statements. Any policy statement must be adhered to, and any deviations should be documented and approved within an organization’s risk management team.These key policy statements should be in the IR policy:

- Statement regarding executive-level commitment

- Purpose, scope, and objectives of the policy

- Definitions of key terms, including the difference between a security incident and security event

- Organizational structure

- Incident severity levels

- Statement on the necessity to prioritize security incidents when multiple incidents, events, or business evolutions are occurring

- Reporting and communication requirements

- Key performance indicators and metrics

Standards

The standards document will provide a bit more detail about the requirements for fulfilling the policy, and should also outline approved tools, technology, and techniques that can be utilized within the IR program.

It should be noted that while the statements within a standards document need to be adhered to with the same rigor as the policy, in some cases, especially with tools, techniques, and technologies, utilizing the specific approved tools may not be possible. This is where a key activity within incident response comes into play: documentation, documentation, and more documentation. All responders should clearly document what they are doing, when they are doing it, and what the outcomes were.

Overall, exceptions to the standard should be documented and tracked within the risk management program; however, if a remote office cannot utilize the “approved” forensic tool for checking a system in the middle of an incident, the standards should be designed so that the Incident Response Manager has the authority to provide an exception. This ensures that the person executing the action documents all of the steps they took to be able to gather and reproduce any evidence in a sound manner.

The types of information contained within the standards document should include:

- Tools and technologies that are approved for use at any time within an incident—these should be specified by name and version number

- Techniques used to gather evidence or analyze systems. In the standards document, these techniques should only be outlined at a high level. The details of the technique should be included in an applicable procedure or guideline.

- Detailed listing and descriptions of the different incident types

- Explanation of the order of prioritization for different incident types

Procedures and guidelines

These documents are the heart of the actual incident response activities. Procedures and guidelines should be written as detailed as possible. While the core of the incident response team may be able to acquire the image of a Windows laptop in their sleep, there may be other staff members that need to help out in a moment’s notice. Consider if, in the middle of a large incident, you have to get a non-technical person in a remote office to get you an image of a laptop. Having step-by-step instructions can mean getting the image to analyze in a few hours vs. getting it in a few days via the shipping department.

I am also of the mindset that creating detailed, step-by-step procedures or workflows can help staff get the basic steps done quickly and thus free themselves up to dig into the findings deeper to better understand what is going on. For example, within an email phishing workflow, I would identify the first steps, such as getting the headers, performing WHOIS on the domains in the headers, investigating any URLs with online tools, performing searches for the SHA256 of any attachments, and considering what should be documented in a report. Once those steps are completed, the analyst can then use their experience and expertise to identify the level of threat or determine that this may be a bigger event than a simple phish. Having the first handful of steps documented in detail allows the analyst to get through the basic stuff in about 15 minutes vs. an hour.

The following are some key items that should be considered for the procedures and guidelines documents:

- Workflows should be established for the different types of incidents or events that will be received (e.g. a workflow to respond to a targeted phishing campaign against the company or a workflow to detail the steps a responder would need to take when an alert is generated from the central SIEM).

- Evidence gathering and handling techniques should be documented in extreme detail so that even a non-technical person can gather evidence in a sound manner.

- Checklists and flow charts are excellent to use within procedures and guidelines.

- Forensic analysis steps should be documented in enough detail to allow the person performing the analysis to get the key steps done quickly.

- Preferences for communications within the team and with external entities should be outlined.

- Detailed steps to take with the specific technology deployed within the organization should be recorded (e.g. how to utilize the Malwarebytes Cloud Platform to export key data that needs to be analyzed to determine the extent of the incident).

Conclusion

Incident response has been a core information security tenant for many years and continues to be an important part of an organization’s information security program. New regulations, such as GDPR, continue to press the need for a solid, documented, tested, and robust IR program.

Your company’s incident response program does not need to be complicated, but it does need to be supported by executive-level leadership, staffed by trained and experienced personnel or outsourced to a reliable and competent MSSP, regularly tested for completeness and competency, and well-documented so an organization does not have to develop a strategy in the heat of the moment. With the right IR program in place, what could end up as an incredibly damaging event for the company might only be a tiny blip.