“Oh no! I’ve got a ransomware notice on my workstation. How did this happen?”

“Let’s figure that out later. First, apply the backup from a few minutes ago, so we can continue to work.”

Now that wasn’t so painful, was it? Having a rollback solution or a recent backup could make this ideal post ransomware–infection scenario possible. But which technology could make this work? And is it possible today?

As we have pointed out before, blockchain technology is not for cryptocurrencies alone. In fact, a few vendors are already offering to use the blockchain to create recent, secured backups.

Backups

With ransomware still one of the most prevalent threats, having backups is one of the most advised strategies against having to pay a ransom. Paying ransoms not only fuels the ransomware industry, it is likely to become illegal in some states and countries.

For backups to be as effective as possible:

- They need to be recent.

- They shouldn’t be destroyed in the same accident or incident as the originals.

- They should be secure against tampering and theft.

- They should be easy to deploy.

To achieve these goals, creating backups in several locations, on different media, and encrypted if necessary goes a long way. This is exactly why using blockchain technology makes sense.

Blockchain

A quick reminder about how blockchain works. Blockchain is a decentralized system that can keep track of changes in the form of a distributed database that keeps a continuously growing list of transactions. Every change in the block results in a different hash value. This provides the opportunity to add a digital signature to each set of data. So, ideally you can be sure that the backup you are about to deploy is recent and hasn’t been tampered with by unauthorized hands.

How it should work

Blockchain technology is a decentralized ledger. Each transaction keeps an identical copy of the previous one. The authenticity of the copies can be confirmed by any of the nodes. The nodes are the “workers” that calculate a valid hash for the next block in the blockchain.

This means that if the first block would hold an encrypted copy of all the files you use today, each next block would include a copy of that set plus all the changes that have been made before the next hash that was accepted by the network of nodes. And each next block would hold all the information in the previous one plus all the changes since then.

Since every node has access to the list of changes, this makes the process completely transparent. Every transaction is recorded, and adding a fingerprint hardens the process against tampering. The architecture of the blockchain makes it impossible to manipulate or change the outcome, and it takes consensus from the nodes to create a legal “fork.”

“Fork” is the term used to describe the situation where two or more valid chains of blocks exist. Or better said, where two blocks of the same height, or with the same block number in the following order, exist at the same time. In a normal situation, the majority decides for one block as the foundation for the rest of the chain and the other fork is abandoned. Sometimes forks are used on purpose to split off a chain for a change in protocol. These are called “hard forks.”

Possible additional features

Timestamps: A backup method using this kind of blockchain technology could also be used as legal proof that a document has not been changed since the time it was included in the backups.

History of changes: A similar method can also be used to keep track of the authorized changes that were made to a document, and record when they took place and who made them.

Pitfalls

Companies looking to deploy blockchain technology to create secure backups need to heed a few pitfalls, especially if they intend to limit the number of nodes to keep them inside the company.

Small networks are vulnerable to attacks by the majority. Blockchain technology is constructed so that the majority decides. And if you can find a way to provide more than half of the computing power active on the network, you can create your own false fork. In cryptocurrencies, such an attack can allow double spending, which leaves one receiving end in the cold. Some cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin Gold (BTG) have found out the hard way that these so-called 51 percent attacks can work. It cost exchanges several millions of dollars.

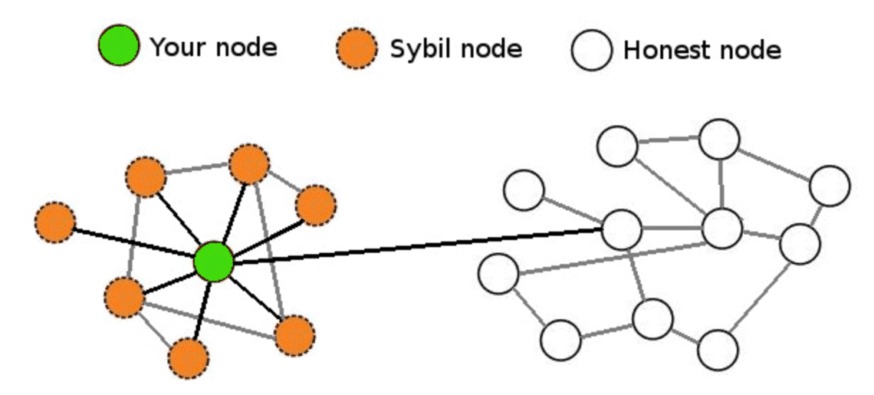

Another possible problem with keeping the number of nodes small is the Sybil attack. A Sybil attack happens when a node in a network uses multiple identities. This is a procedure that can allow an attacker to outvote honest nodes by controlling or creating a majority. Where a 51 percent attack would be solely based on computing power, some networks use a factor called “reputation” as an additional weighing factor for the influence of the nodes.

Your node controls the Sybil nodes attempting to gain total control. Image courtesy of CoinCentral.

User behavior is always a concern. You can create the safest backup system, but a disgruntled employee could frustrate the whole effort. And insiders do not even have to have bad motives to corrupt the system. They may do it out of ignorance or with the best intentions. They may want to sweep something under the rug and unwittingly remove or corrupt more than they expected.

Deleted files could be a problem in some setups. This is something to keep in mind. Having the hash of the deleted file and the date when it was removed may not always be satisfactory. Even if you know when and by whom a file was deleted, that will not bring it back. Depending on the way the backup system is set up, this may be solved with some digging in old backups, or they may be lost forever.

The underlying problem for this is: Do you want every version of every document to be available at all times, or is it okay to have the original and the latest version with a historical overview of when it was changed and by whom? Ideally there should be some middle ground, for example, complete backups once a year and incremental backups done by the blockchain.

Large node networks

To prevent any type of majority attack, companies could decide to use larger, established networks like the Ethereum Project, but this may collide with policies of not sharing any kind of data outside their own network. Even if it is only the hashes and timestamps of the filesystem, this could clue others into what’s going on. And the costs for the nodes calculating the hashes (the miners) could prove to be more expensive than current backup solutions.

So when can we expect to see this happening?

I think we will see more progress made in this field in the near future. Incremental backup and keeping track of changes has blockchain written all over it. But a viable solution should have a large network behind it. And there are some other pitfalls to keep in mind when designing and setting up such a backup system. It may not be ready yet to be your only solution, but it seems to be an ideal fix to have incremental backups on a blockchain combined with full backups at set intervals.