Nine months ago, Malwarbytes recommitted itself to detecting invasive monitoring apps that can lead to the excessive harm of women—most commonly known as stalkerware. We pledged to raise public awareness, reach out to advocacy groups, and share samples and intelligence with other security vendors.

Now, for International Women’s Day (March 8), we decided to take measure of our efforts, examining the effects of our campaign and outreach, as well as the formation of the Coalition Against Stalkerware, of which we were a founding member. Have we actually made a difference?

As a refresher, or for those that haven’t been following along: Stalkerware and other monitoring apps can allow a user to look through someone else’s text messages, record their phone calls, turn on their phone’s cameras and microphones, rifle through their private files, peer into their search history, and track their GPS location—all without consent.

We know that stalkerware, monitoring apps, and others with spyware-like capabilities present clear potential for privacy violations. However, these apps and other Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as smart thermostats, doorbells, and locks, have been tied to multiple cases of physical stalking, cyberstalking, and domestic violence. In fact, according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline, victims of digital abuse and harassment are two times as likely to be physically abused, two-and-a-half times as likely to be psychologically abused, and five times as likely to be sexually coerced.

While many stalkerware apps market or classify themselves as parental monitoring apps, their technical capabilities are essentially the same—sometimes on par with the level of surveillance perpetrated by nation-state actors. Worse, when put into the hands of domestic abusers, they can totally dismantle a survivor’s life, revealing their location if they’re trying to escape or uncovering their private messages if they’re attempting to discuss a safety plan.

Yet, for all its potential for emotional and physical harm, stalkerware has often been swept under the rug by many in the cybersecurity community. Most antivirus companies do not detect monitoring apps; or if they do, they use weak language indicating the threat is not as severe as malware.

That’s what caused Electric Frontier Foundation Director of Cybersecurity Eva Galperin to start calling out antivirus companies in April 2019 for better protection. And that’s why we stood up with her—to double down on what we started more than five years ago with our own stalkerware detection efforts.

Let’s take a look at how we’re doing so far. These are the numbers on stalkerware.

Stalkerware public awareness

While we have written about monitoring apps’ potential to be used for domestic abuse since 2014 (and detected those apps in our Malwarebytes for Android program), we first aimed to raise public awareness of stalkerware by publishing more than 10 articles on the topic since June 2019, including how to protect against stalkerware, what domestic abuse survivors should do if they find stalkerware on their phone, and the difficulties of pursuing legal action for stalkerware victims.

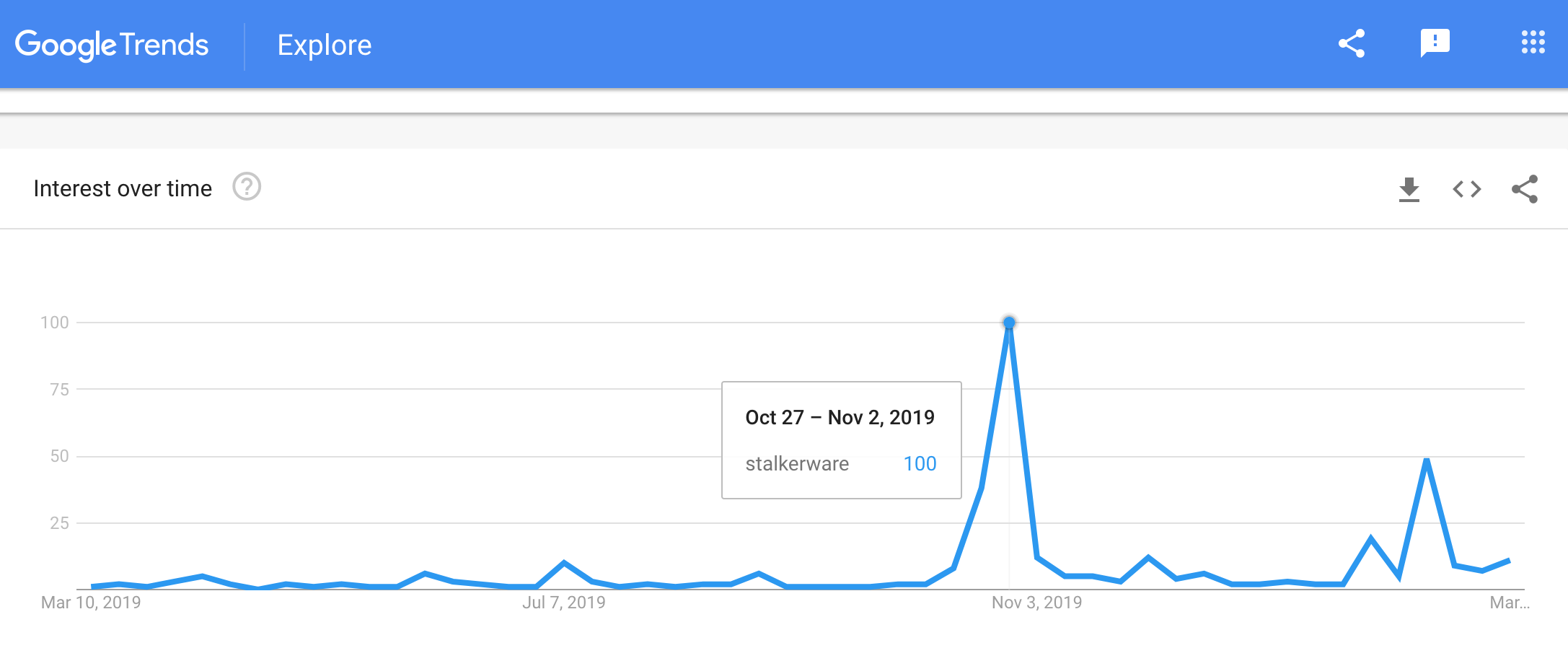

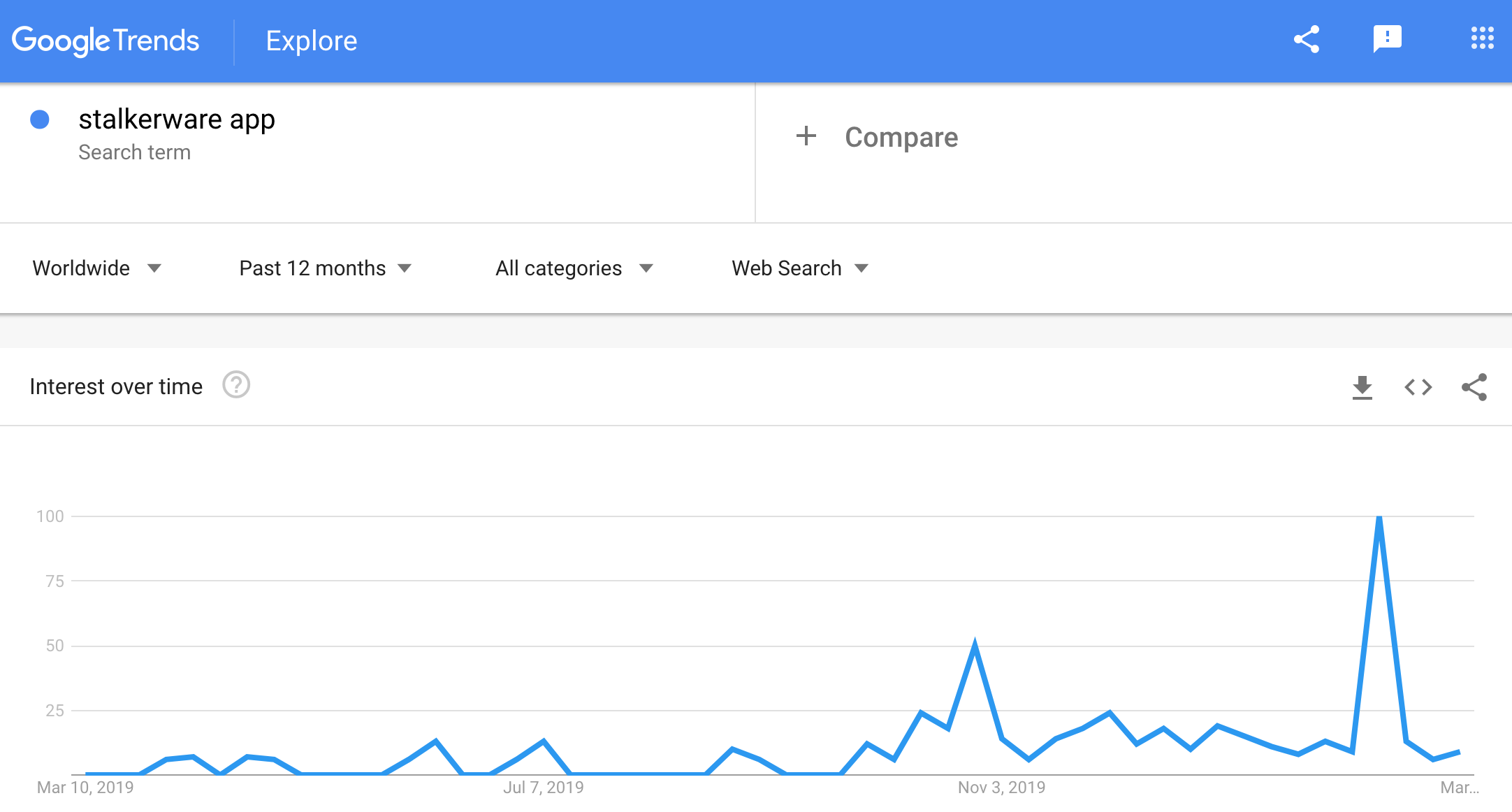

In total, our articles have been read nearly 65,000 times. The terms “stalkerware,” “stalkerware app” and “stalkerware Android” have gained a bit of momentum in Google search over the last year, showing signs of life in June 2019, the month we published our first article of the campaign. A small spike in July also coincides with our own coverage, as well as Google Play pulling seven stalkerware apps from its store. The biggest bump in overall awareness was in late October and early November 2019, when National Cyber Security and National Domestic Violence Awareness months coincided with the FTC bringing its first stalkerware case, fining app developers for violations.

Mobile monitor and spyware categories: global detections of stalkerware

Despite the popular “stalkerware” label, Malwarebytes does not use the term to classify app detections within our product, as murky marketing techniques can often make distinguishing between stalkerware, workplace, or parental monitoring apps difficult. Instead, we look at the technical capabilities of the software and detect stalkerware apps as either belonging to the monitor category or spyware.

From March 1, 2019 to March 1, 2020, Malwarebytes detected monitor apps 55,038 times on Malwarebytes for Android user devices. During the same time period the year before, monitor apps were detected 44,116 times. That’s an increase of more than 10,000 detections in a single year.

We must be clear: The rise in monitor detections does not automatically guarantee a rise in the use of these apps. Because Malwarebytes improved its capabilities to find monitoring apps, our detection volume did increase. We bolstered our data set independently, but also worked with other cybersecurity vendors in the Coalition Against Stalkerware to improve our results.

However, a February 2020 survey by Norton LifeLock on “online creeping” found that 49 percent of respondents admitted to “stalking” their partner or ex online without their knowledge or consent—a number that suggests a general acceptance of online stalking behavior today. Does that mean there are more developers and users of monitoring apps than there were before? We would need to conduct a meta-study and include more data points than our own telemetry to determine that truth. What we do know is that today, Malwarebytes detects 2,745 variants of monitor apps, an increase of nearly 1,000 from the year before.

Interestingly, from March 1, 2019 to March 1, 2020, Malwarebytes for Android registered 1,378 spyware detections on user devices. In the previous year, however, Malwarebytes detected spyware 2,388 times for users in the same group. In fact, although we now detect 318 variants of spyware apps for Android devices—an increase of almost 40 from the year before—our detections still decreased year over year.

The decrease in spyware detections perhaps points to something different—a decision to shy away from making and utilizing these tools. Whereas stalkerware-type apps have seen little enforcement, either from the government or from individuals and companies, spyware apps have received deeper scrutiny. Just this week, WhatsApp moved forward with its lawsuit against one major spyware developer.

In looking at our data, we also discovered these threats in nearly every part of the world. Malwarebytes detected monitoring APKs in the US, India, Indonesia, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Ireland, France, Russia, Mexico, Italy, Canada, Germany, Bangladesh, Australia, and the United Arab Emirates. The US represented the largest share of detections, but admittedly, it also represents the largest share of our user base.

While our telemetry shows that monitoring apps continue to plague users everywhere, the data does not show the broader relationship between these types of apps and stalking, cyberstalking, and domestic violence.

Monitoring apps and domestic violence

According to Danielle Citron, professor of law at Boston University School of Law, monitoring apps, or what she calls “cyber stalking” apps, have been tied to multiple cases of domestic violence and abuse. As she wrote in her 2015 paper “Spying Inc.”

“A woman fled her abuser who was living in Kansas. Because her abuser had installed a cyber stalking app on her phone, her abuser knew that she had moved to Elgin, Illinois. He tracked her to a shelter and then a friend’s home where he assaulted her and tried to strangle her. In another case, a woman tried to escape her abusive husband, but because he had installed a stalking app on her phone, he was able to track down her and her children. The man murdered his two children. In 2013, a California man, using a spyware app, tracked a woman to her friend’s house and assaulted her.”

Further, according to the NortonLifeLock survey, the use of stalkerware-type apps is just one of several behaviors that Americans engage in to check in on their ex and current romantic partners online.

The Online Creeping Survey, which included responses from more than 2,000 adults in the US, showed that 1 in 10 Americans admitted to using stalkerware-type apps against their ex or current romantic partners. The survey also found that 21 percent of respondents looked through a partner’s device search history without permission, and 9 percent said they created a fake social media profile to check in on an ex or current partner.

Kevin Roundy, technical director for NortonLifeLock, warned about these behaviors.

“Some of the behaviors identified in the NortonLifeLock Online Creeping Survey may seem harmless, but there are serious implications when this becomes a pattern of behavior and escalates, or when stalkerware and creepware apps get in the hands of an abusive ex or partner,” Roundy said.

As Malwarebytes reported last year, some of these behaviors are closely associated with the crimes of stalking and cyberstalking in the United States. Use of monitoring or spyware apps can create conditions in which domestic abusers can follow their partners’ GPS locations and allow them to look at their private conversations through texts and emails. For domestic abuse survivors trying to escape a dangerous situation, stalkerware can place them at an even greater risk.

Unfortunately, much of the behavior related to stalking and cyberstalking disproportionately harms women.

According to a national report of about 13,000 interviews conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 15.2 percent of women and an estimated 5.7 percent of men have been stalked in their lifetime.

Similar data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics showed nearly the same discrepancy. In a six-month period, of more than 65,000 Americans interviewed, 2.2 percent of women reported they had been stalked, while 0.8 percent of men reported the same.

While stalking victims include both men and women, the data from both studies shows that women are stalked roughly 270 percent more often than men.

What else can we do?

The stalkerware problem is tangled and complex. Makers of these types of apps often skirt government enforcement actions—with only two developers receiving federal consequences in the past six years. Users of these apps can vary from individuals who consent to being tracked to domestic abusers who never seek consent.

And the way in which these apps can be used can violate both Federal and state laws, yet, when the apps are used in conjunction with stalking and cyberstalking, the victims of these crimes often shy away from engaging with law enforcement to find help. Even if victims do work with police, they often have one priority—stopping the harm, not filing prolonged lawsuits against their stalkers or abusers.

Though this threat may appear slippery, there is much that we in the cybersecurity community can do. We can better detect these types of threats and inform users about their dangers. We can train domestic abuse advocates about device security for themselves and for the survivors they support—something Malwarebytes has already done and will continue doing. We can gather a growing coalition of partners to share intelligence and samples to collectively fight.

We can work with law enforcement on improving their own cybersecurity awareness and training, demonstrating the ways in which technology can and has been abused or developing a collaborative taxonomy for smart, efficient reporting. Finally, we can partner with domestic violence researchers to better understand what domestic abuse survivors need for digital security and protection—and then implement those changes.

We make the technology. We can make it better protect users everywhere.