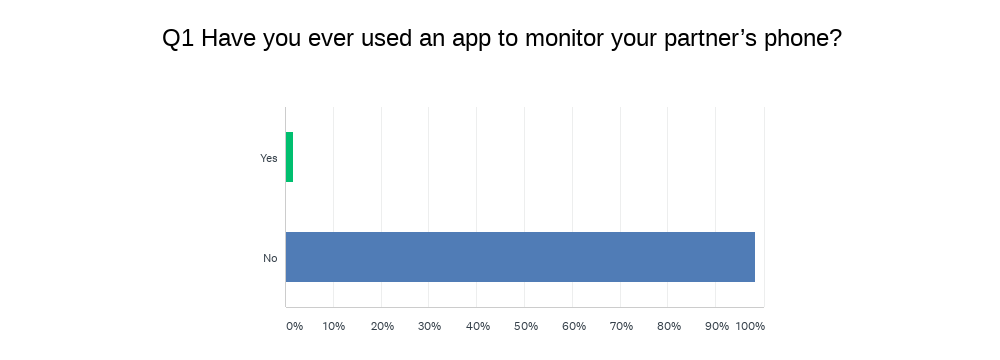

Back in July, we sent out a survey to Malwarebytes Labs readers on the subject of stalkerware—the term used to describe apps that can potentially invade someone’s privacy. We asked one question: “Have you ever used an app to monitor your partner’s phone?”

The results were reassuring.

We received 4,578 responses from readers all over the world to our stalkerware survey and the answer was a resounding “NO.” An overwhelming 98.23 percent of respondents said they had not used an app to monitor their partner’s phone.

For our part, Malwarebytes takes stalkerware seriously. We’ve been detecting apps with monitoring capabilities for more than six years—now Malwarebytes for Windows, Mac, or Android detects and allows users to block applications that attempt to monitor your online behavior and/or physical whereabouts without your knowledge or consent. Last year, we helped co-found the Coalition Against Stalkerware with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the National Network to End Domestic Violence, and several other AV vendors and advocacy groups.

It stands to reason that a readership comprised of Malwarebytes customers and people with a strong interest in cybersecurity would say “no” to stalkerware—we’ve spoken up about the potential privacy concerns associated with using these apps and the danger of equipping software with high-grade surveillance capabilities for a long time. We didn’t want to assume everyone agreed with us, but the data from our stalkerware survey shows our instincts were right.

No to stalkerware

Beyond a simple yes or no, we also asked our survey-takers to explain why they answered the way they did. The most common answer by far was a mutual respect and trust for their partner. In fact, “respect,” “trust,” and “privacy” were the three most commonly-used words by our participants in their responses:

“My partner and I share our lives … To monitor someone else’s phone is a tragic lack of trust.”

Many of those surveyed cited the Golden Rule (treat others the way you want to be treated) as their reason for not using stalkerware-type apps:

“I wouldn’t want anyone to monitor me so I therefore I would not monitor them.”

Others saw it as a clear-cut issue of ethics:

“People are entitled to their privacy as long as they do not do things that are illegal. Their rights end at the beginning of mine.”

Some respondents shared harrowing real-life accounts of being a victim of stalkerware or otherwise having their privacy violated:

“I have been a victim of stalking several times when vicious criminals used my own surveillance cameras to spy on my activity then used it to break into my apartment.”

Stalkerware vs. location sharing vs. parental monitoring

Many of those surveyed, answering either yes or no, made a distinction between stalkerware-type apps writ large and location-sharing apps like Apple’s Find My Phone and Google Maps. Location sharing was generally considered acceptable because users volunteered to share their own information and sharing was limited to their current location.

“My wife & myself allow Apple Find My Phone to track each other if required. I was keen that should I not arrive home from a run, she could find out where I was in the case of a health issue or accident.”

Also considered okay by our respondents were the types of parental controls packaged in by default with their various devices. Many respondents specifically mentioned tracking their child’s location:

“It would not be ok with me if someone was monitoring me and I would never do it to anyone else, the only thing I would like is be able to track my child if kidnapped.”

Some parents admitted to using monitoring of some kind with their children, but it wasn’t clear how far they were willing to go and if children were aware they were being monitored:

“The only reason I have set up parental control for my son is for his safety most importantly.”

This is the murky world of parental-monitoring apps. On one end of the spectrum there are the first-party parental controls like those built into the iPhone and Nintendo Switch. These controls allow parents to restrict screen time and approve games and additional content on an ad hoc basis. Then there are third-party apps, which provide limited capabilities to track one thing and one thing only, like, say, a child’s location, or their screen time, or the websites they are visiting.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are apps in the same parental monitoring category that can provide a far broader breadth of monitoring, from tracking all of a child’s interactions on social media to using a keylogger that might even reveal online searches meant to stay private.

You can hear more about our take on these apps in our latest podcast episode, but the long and the short of it is that Malwarebytes doesn’t recommend them, as they can feature much of the same high-tech surveillance capabilities of nation-state malware and stalkerware, but often lack basic cybersecurity and privacy measures.

Who said ‘yes’ to stalkerware?

Of course, our stalkerware survey analysis would not be complete without taking a look at the 81 responses from those who said “yes” to using apps to monitor their partners’ phone.

Again, the majority of respondents made a distinction between consensual location-sharing apps and the more intrusive types of monitoring that stalkerware can provide. Many of those who answered “yes” to using an app to monitor their partner’s phone said things like:

“My wife and I have both enabled Google’s location sharing service. It can be useful if we need to know where each other is.”

And:

“Only the Find My iPhone app. My wife is out running or hiking by herself quite often and she knows I want to know if she is safe.”

Of the 81 people who said they use apps to monitor their partners’ phones, only nine cited issues of trust, cheating, “being lied to” or “change in partner’s behavior.” Of those nine, two said their partner agreed to install the app.

NortonLifeLock’s online creeping study

The results of the Labs stalkerware survey are especially interesting when compared to the Online Creeping Survey conducted by NortonLifeLock, another founding member of the Coalition Against Stalkerware.

This survey of more than 2,000 adults in the United States found that 46 percent of respondents admitted to “stalking” an ex or current partner online “by checking in on them without their knowledge or consent.”

Twenty-nine percent of those surveyed admitted to checking a current or former partner’s phone. Twenty-one percent admitted to looking through a partner’s search history on one of their devices without permission. Nine percent admitted to creating a fake social media profile to check in on their partners.

When compared to the Labs stalkerware survey, it would seem that online stalking is considered more acceptable when couched under the term “checking in.” For perspective, if one were to swap the word “diary” for “phone,” we don’t think too many people would feel comfortable admitting, “Hey, I’m just ‘checking in’ on my girlfriend/wife’s diary. No big deal.”

Stalkerware in a pandemic

Finally, we can’t end this piece without at least acknowledging the strange and scary times we’re living in. Shelter-in-place orders at the start of the coronavirus pandemic became de facto jail sentences for stalkerware and domestic violence victims, imprisoning them with their abusers. No surprise, The New York Times reported an increase in the number of domestic violence victims seeking help since March.

For some users, however, the pandemic has brought on a different kind of suffering. One survey respondent best summed up the current malaise of anxiety, fear, and depression:

“No partner to monitor lol.”

We like to think, dear reader, that they’re not laughing at themselves and the challenges of finding a partner during COVID. Rather, they’re laughing at all of us.

Stalkerware resources

As mentioned earlier, Malwarebytes for Windows, Mac, or Android will detect and let users remove stalkerware-type applications. And if you think you might have stalkerware on your mobile device, be sure to check out our article on what to do when you find stalkerware or suspect you’re the victim of stalkerware.

Here are a few other important reads on stalkerware:

Stalkerware and online stalking are accepted by Americans. Why?

Stalkerware’s legal enforcement problem

Awareness of stalkerware, monitoring apps, and spyware on the rise