Ransomware is still going strong and infecting countless PCs. We happened to stumble upon an interesting sample part of the Urausy family which bypassed detection on all major antivirus products for almost an entire day before slowly being detected. In this post we will give some information on its background (where it came from) and a detailed analysis of its binary.

Malware distribution

We first caught this piece of malware in our honeypots on 2013-03-06 at 09:09. It came from a drive-by download attack:

This is a new Exploit Kit, dubbed neutrino, identified in the wild by Kafeine. Its landing page follows a certain pattern in its URL: [domain name]/l[random letters]?f[random letters]=[random numbers].

Examples: hxxp://{removed}/lddinxkq?fhdubnro=8866005 hxxp://{removed}/luvvy?fwchvcdyrsy=8422752

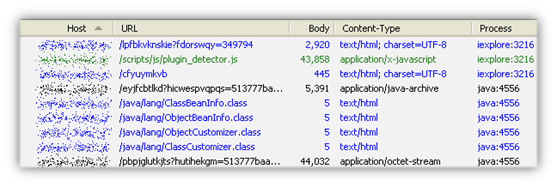

It uses two Java vulnerabilities:

CVE-2012-1723

CVE-2013-0431

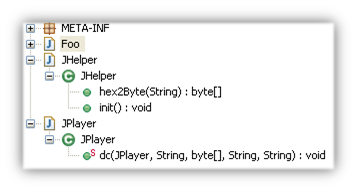

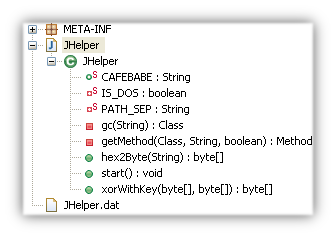

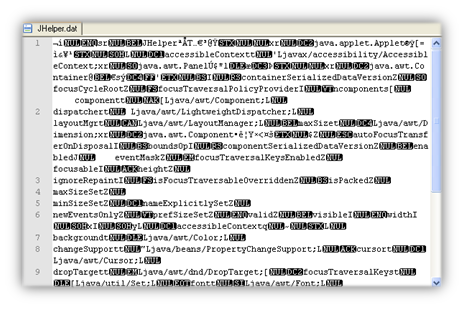

In CVE-2013-0431, the malicious Java Applet bypasses the security manager for Java version 7 update 11 by using a malicious serialized file, Jhelper.dat (should really be a .ser file extension but works the same).

While serialization and deserialization are legitimate features, they can be exploited to bypass security checks. Essentially, when Oracle introduced the new security levels withVersion 7 Updated 10, they missed that Applets using serialization can avoid calling an important method known as ‘fireAppletSSVValidation’. In plain English: malicious applets can run without any warnings or user interaction.

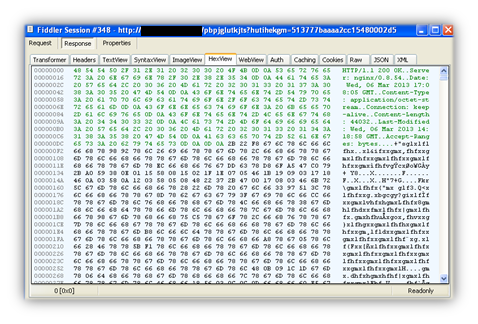

Following exploitation, a malware binary is downloaded by the java process and as you can see in the picture below, is encrypted:

This practice is becoming more and more common these days as it makes detection by looking at traffic packets more difficult. The file is swiftly decrypted by the java applet which in turns launches it.

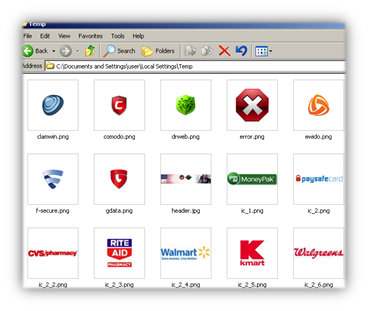

Upon execution the binary connects to a remote server (hxxp://{removed}/news/ulul-ululul-ulululjbma-dkqvdikopislasycnzmzpzapieoqnveqxubpdyflslylbp-lmaa_perpih-xpns-quie.html) and downloads the ransomware interface directly onto the victim’s machine . Again, the bad guys are using obfuscation techniques to hide the content of the file. It includes images, CSS and an index.html file which are uncompressed in the user’s temp folder:

The malware binary then launches the (local) ransomware page:

Why use a local web page rather than an actual website? Perhaps because it is more resilient (a remote site could be taken down).

Technical File Analysis

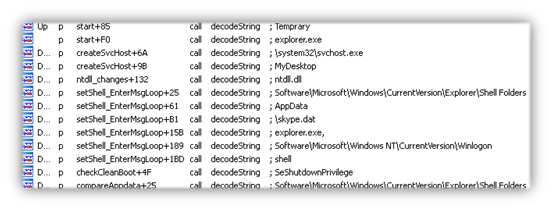

Analysis reveals the ransomware binary to be a skype.dat variant that’s commonly seen in the wild. It’s called this because the ransomware renames itself to “skype.dat” and is placed in the user’s %appdata% folder, along with a configuration file called “skype.ini”. The skype.dat ransomware has nothing to do with the legitimate Skype program that millions of people use for VoIP communication.

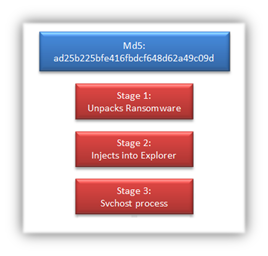

The skype.dat ransomware takes advantage of multiple Windows processes and leverages native system API calls to facilitate its execution. Below is a chart describing the ransomware’s flow of execution.

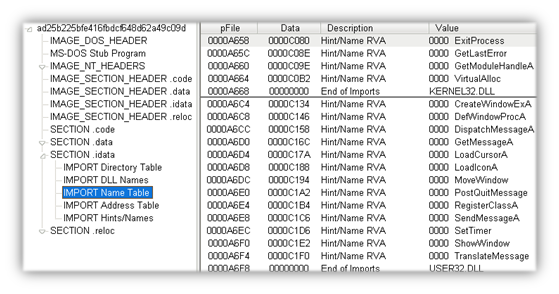

Stage1 The skype.dat unpacker varies across ransomware samples. The sample we analyzed from the neutrino exploit payload has a very small Import Address Table (IAT) that doesn’t immediately reveal a lot of malicious intent, except perhaps VirtualAlloc. This call is legitimately used by Windows to allocate memory within the virtual address space of a process; however, malware often makes use of this call to create a new memory for unpacked code to reside. What you don’t see in this IAT that most packed malware has is LoadLibrary and GetProcAddress. These two calls allow the malware to access additional functions in other dynamic-link libraries (DLLs).

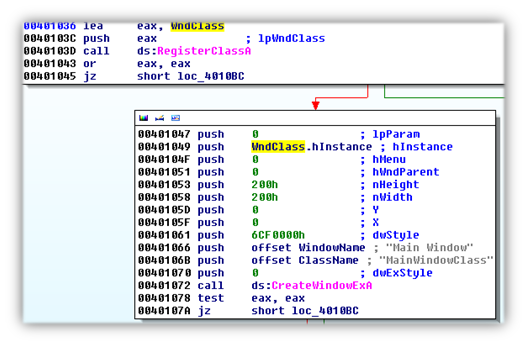

Let’s start looking at the code and see what we find. The ransomware begins by registering a window class by calling RegisterClassA, which creates the WNDCLASS structure containing a window procedure. After the window is created using CreateWindowExA, the window procedure is called repeatedly while the window is being created.

The window procedure contains a loop that intercepts messages while the window is created. When the WM_CREATE message is sent to the application, the call to VirtualAlloc occurs. Like we originally suspected, the ransomware’s real code resides here after being de-obfuscated using a custom routine. For more about obfuscation, make sure to check out Obfuscation: Malware’s best friend on the Unpacked blog.

Stage2 The ransomware starts building a new IAT that’s much larger than before and checks for the presence of a debugger using ZwQueryInformationProcess. It’s quite common for malware to check for a debugger to see if it’s being analyzed, this sample is no different. Furthermore, the ransomware encodes all of its strings to make it more difficult to analyze.

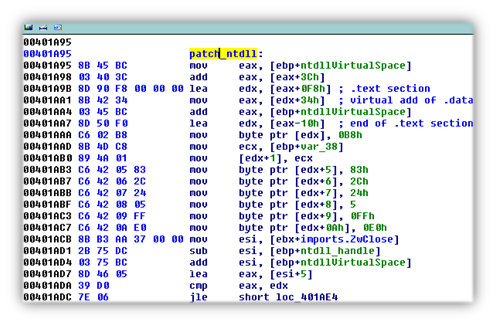

The process id (PID) for Windows Explorer (explorer.exe) is retrieved since we’ll be targeting that process in this stage. A modified version of ntdll.dll is injected into Explorer, replacing the original one. This modified DLL hijacks the ZwClose API call and references new code that’s mapped within explorer.exe.

DLL injection has been used for a long time to run code within the address of another process, usually to escalate privileges. This particular injection method is interesting, however, in that it modifies a native system DLL and API to achieve its results and continue execution within another process.

The code within Explorer creates a Windows service host process (svchost.exe). This process is created in a suspended state and only resumed after code is injected via CreateRemoteThread. This process is where the ransomware will operate.

Stage3 The ransomware registers another window class and creates a non-overlapping window on a new desktop. The window procedure waits until the window is created and creates a Web Browser object along with five threads. As seen in a lot of ransomware, some of these threads limit the user’s interaction with the Operating System by preventing access to the Desktop and killing any launched Task Manager processes.

From here the ransomware performs an environment survey of the host and crafts a URL for downloading. Part of the host survey involves checking to see if the following AV processes are running on the host.

- a2servece.exe

- guardxservice.exe

- aawService.exe

- avp.exe

- arcamainsv.exe

- mcsvhost.exe

- avastsvc.exe

- ekrn.exe

- avgcsrvx.exe

- ccsvchst.exe

- avguard.exe

- winssnotify.exe

- vsserv.exe

- msmpeng.exe

- clamWin.exe

- acs.exe

- clpsls.exe

- pavprsrv.exe

- dwengine.exe

- scfservice.exe

- ewidoguard.exe

- coreserviceshell.exe

- fpavserver.exe

- vba32ldr.exe

- fsdfwd.exe

- vbcmserv.exe

- gdscan.exe

- iswsvc.exe

The ransomware then contacts a malicious URL and downloads files needed to operate. The ransom page demands users enter a Moneypak or Ukash code. This ransomware will also survive a reboot by adding skype.dat as a default shell upon system startup.

Conclusion

The skype.dat ransomware continues to be successful at locking down computers, preventing users from accessing their files. It seems unusual that this particular sample has evaded virus detection, although the ransomware’s original IAT is very small and doesn’t overtly indicate foul play. Crafting a binary in this way helps to defeat heuristic analysis from Antivirus scanners, and primarily why malware authors choose to obfuscate their programs.

If you become infected by ransomware, it’s critically important to remember not to pay the ransom. While this may restore access to your computer, you can never guarantee that criminals are going to live up to their end of the bargain. Remember to check out our ransomware blog for instructions on how to remove ransomware should you become infected with skype.dat.

Report prepared by: Jerome Segura, Senior Security Researcher Joshua Cannell, Malware Intelligence Analyst