One of the Holy Grails for malware authors is a perfect way to impersonate a legitimate process. That would allow them to run their malicious module under the cover, being unnoticed by antivirus products. Over the years, various techniques have emerged in helping them to get closer to this goal. This topic is also interesting for researchers and reverse engineers, as it shows creative ways of using Windows APIs.

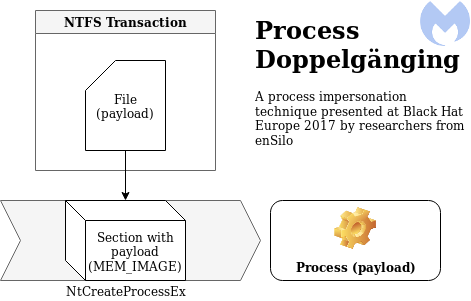

Process Doppelgänging, a new technique of impersonating a process, was published last year at the Black Hat conference. After some time, a ransomware named SynAck was found adopting that technique for malicious purposes. Even though Process Doppelgänging still remains rare in the wild, we recently discovered some of its traits in the dropper for the Osiris banking Trojan (a new version of the infamous Kronos). After closer examination, we found out that the original technique was further customized.

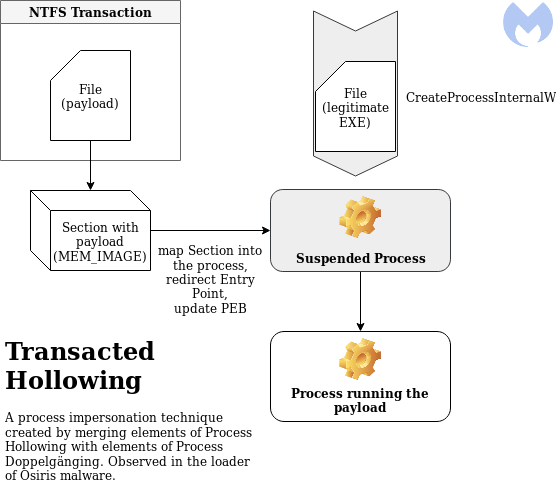

Indeed, the malware authors have merged elements from both Process Doppelgänging and Process Hollowing, picking the best parts of both techniques to create a more powerful combo. In this post, we take a closer look at how Osiris is deployed on victim machines, thanks to this interesting loader.

Overview

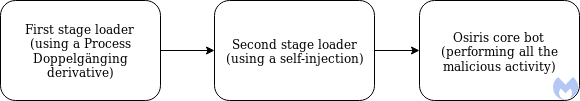

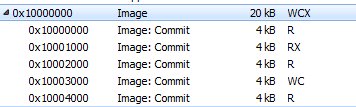

Osiris is loaded in three steps as pictured in the diagram below:

The first stage loader is the one that was inspired by the Process Doppelgänging technique but with an unexpected twist. Finally, Osiris proper is delivered thanks to a second stage loader.

Loading additional NTDLL

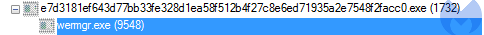

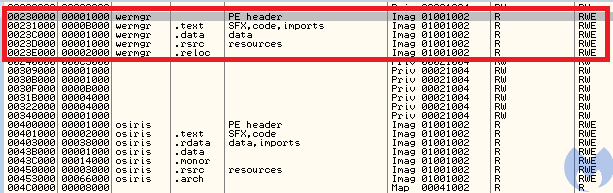

When ran, the initial dropper creates a new suspended process, wermgr.exe.

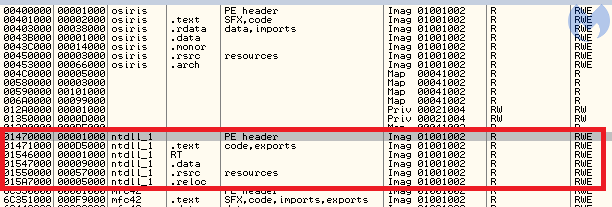

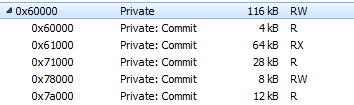

Looking into the modules loaded within the injector’s process space, we can see this additional copy of NTDLL:

This is a well-known technique that some malware authors use in order to evade monitoring applications and hide the API calls that they use. When we closely examine what functions are called from that additional NTDLL, we find more interesting details. It calls several APIs related to NTFS transactions. It was easy to guess that the technique of Process Doppelgänging, which relies on this mechanism, was applied here.

NTDLL is a special, low-level DLL. Basically, it is just a wrapper around syscalls. It does not have any dependencies from other DLLs in the system. Thanks to this, it can be loaded conveniently, without the need to fill its import table.

Other system DLLs, such as Kernel32, rely heavily on functions exported from NTDLL. This is why many user-land monitoring tools hook and intercept the functions exported by NTDLL: to watch what functions are being called and check if the process does not display any suspicious activity.

Of course malware authors know about this, so sometimes, in order to fool this mechanism, they load their own, fresh and unhooked copy of NTDLL from disk. There are several ways to implement this. Let’s have a look how the authors of the Osiris dropper did it.

Looking at the memory mapping, we see that the additional NTDLL is loaded as an image, just like other DLLs. This type of mapping is typical for DLLs loaded by LoadLibrary function or its low-level version from NTDLL,

LdrLoadDllUsually, malware authors decide to map the second copy manually, but that gives a different mapping type and stands out from the normally-loaded DLLs. Here, the authors made a workaround: they loaded the file as a section, using the following functions:

- – to open the ntdll.dll file

ntdll.NtCreateFile - – to create a section out of this file

ntdll.NtCreateSection - – to map this section into the process address space

ntdll.ZwMapViewOfSection

This was a smart move because the DLL is mapped as an image, so it looks like it was loaded in a typical way.

This DLL was further used to make the payload injection more stealthy. Having their fresh copy of NTDLL, they were sure that the functions used from there are not hooked by security products.

Comparison with Process Doppelgänging and Process Hollowing

The way in which the loader injects the payload into a new process displays some significant similarities with Process Dopplegänging. However, if we analyze it very carefully, we can see also differences from the classic implementation proposed last year at Black Hat. The differing elements are closer to Process Hollowing.

Classic Process Doppelgänging:

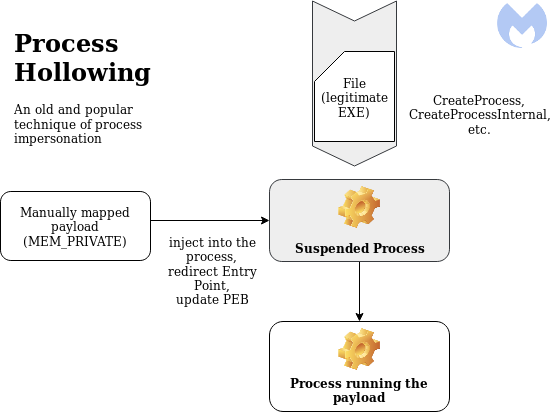

Process Hollowing:

Osiris Loader:

Creating a new process

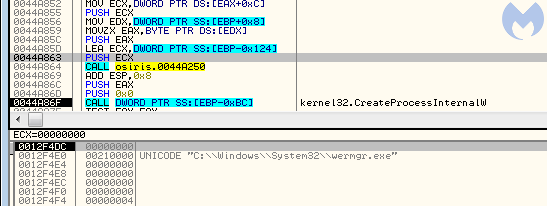

The Osiris loader starts by creating the process into which it is going to inject. The process is created by a function from Kernel32: CreateProcessInternalW:

The new process (wermgr.exe) is created in a suspended state from the original file. So far, it reminds us of Process Hollowing, a much older technique of process impersonation.

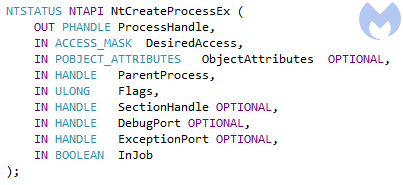

In the Process Dopplegänging algorithm, the step of creating the new process is taken much later and uses a different, undocumented API: NtCreateProcessEx:

This difference is significant, because in Process Doppelgänging, the new process is created not from the original file, but from a special buffer (section). This section was supposed to be created earlier, using an “invisible” file created within the NTFS transaction. In the Osiris loader, this part also occurs, but the order is turned upside down, making us question if we can call it the same algorithm.

After the process is created, the same image (wermgr.exe) is mapped into the context of the loader, just like it was previously done with NTDLL.

As it later turns out, the loader will patch the remote process. The local copy of the wermgr.exe will be used to gather information about where the patches should be applied.

Usage of NTFS transactions

Let’s start from having a brief look at what are the NTFS transactions. This mechanism is commonly used while operating on databases—in a similar way, they exist in the NTFS file system. The NTFS transactions encapsulate a series of operations into a single unit. When the file is created inside the transaction, nothing from outside can have access to it until the transaction is committed. Process Doppelgänging uses them in order to create invisible files where the payload is dropped.

In the analyzed case, the usage of NTFS transactions is exactly the same. We can spot only small differences in the APIs used. The loader creates a new transaction, within which a new file is created. The original implementation used CreateTransaction and from Kernel32. Here, they were substituted by low-level equivalents.

First, a function ZwCreateTransaction from a NTDLL is called. Then, instead of

CreateFileTransactedRtlSetCurrentTransaction along with

ZwCreateFileRtlSetCurrentTransaction with

ZwWriteFile

We can see that the buffer that is being written contains the new PE file: the second stage payload. Typically for this technique, the file is visible only within the transaction and cannot be opened by other processes, such as AV scanners.

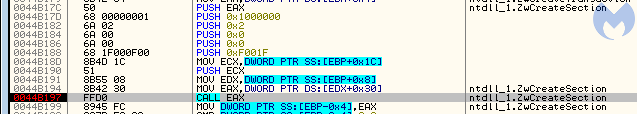

This transacted file is then used to create a section. The function that can do it is available only via low-level API: ZwCreateSection/NtCreateSection.

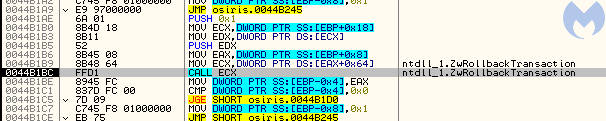

After the section is created, that file is no longer needed. The transaction gets rolled back (by ZwRollbackTransaction), and the changes to the file are never saved on the disk.

So, the part described above is identical to the analogical part of Process Doppelgänging. Authors of the dropper made it even more stealthy by using low-level equivalents of the functions, called from a custom copy of NTDLL.

From a section to a process

At this point, the Osiris dropper creates two completely unrelated elements:

- A process (at this moment containing a mapped, legitimate executable wermgr.exe)

- A section (created from the transacted file) and containing the malicious payload

If this were typical Process Doppelgänging, this situation would never occur, and we would have the process created directly based on the section with the mapped payload. So, the question arises, how did the author of the dropper decide to merge the elements together at this point?

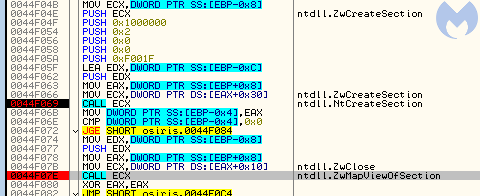

If we trace the execution, we can see following function being called, just after the transaction is rolled back (format: RVA;function):

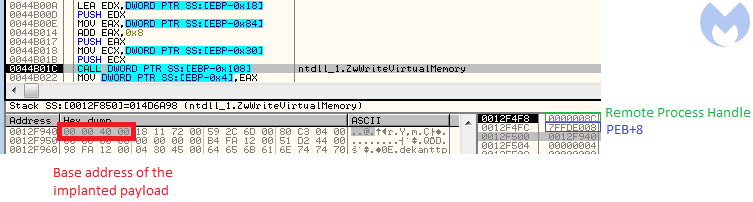

4b1e6;ntdll_1.ZwQuerySection 4b22b;ntdll.NtClose 4b239;ntdll.NtClose 4aab8;ntdll_1.ZwMapViewOfSection 4af27;ntdll_1.ZwProtectVirtualMemory 4af5b;ntdll_1.ZwWriteVirtualMemory 4af8a;ntdll_1.ZwProtectVirtualMemory 4b01c;ntdll_1.ZwWriteVirtualMemory 4b03a;ntdll_1.ZwResumeThread

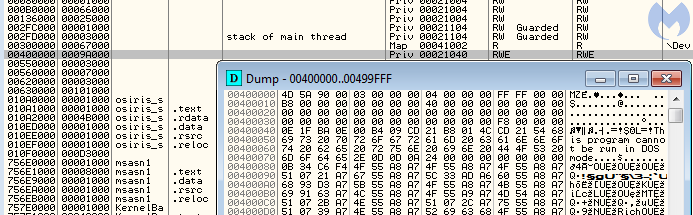

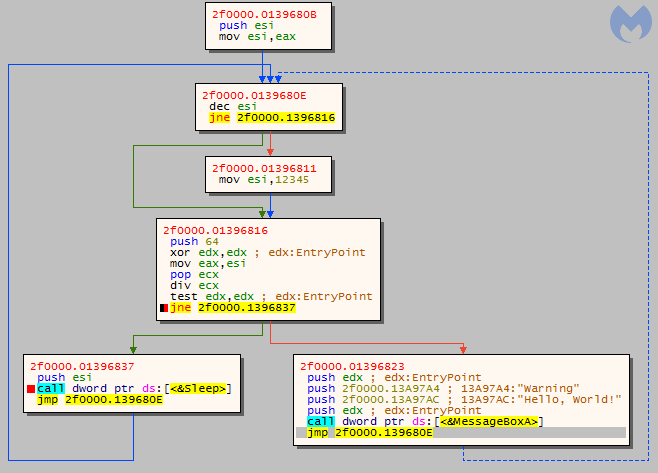

So, it looks like the newly created section is just mapped into the new process as an additional module. After writing the payload into memory and setting the necessary patches, such as Entry Point redirection, the process is resumed:

The way in which the execution was redirected looks similar to variants of Process Hollowing. The PEB of the remote process is patched, and the new module base is set to the added section. (Thanks to this, imports will get loaded automatically when the process resumes.)

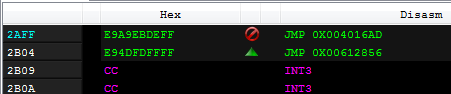

The Entry Point redirection is, however, done just by a patch at the Entry Point address of the original module. A single jump redirects to the Entry Point of the injected module:

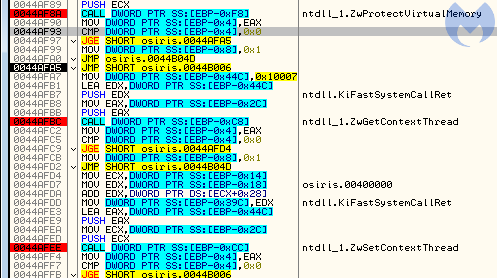

In case patching the Entry Point has failed, the loader contains a second variant of Entry Point redirection, by setting the new address in the thread context (ZwGetThreadContext -> ZwSetThreadContext), which is a classic technique used in Process Hollowing:

Best of both worlds

As we can see, the author merged some elements of Process Doppelgänging with some elements of Process Hollowing. This choice was not accidental. Both of those techniques have strong and weak points, but by merging them together, we get a power combo.

The weakest point of Process Hollowing is about the protection rights set on the memory space where the payload is injected (more info here). Process Hollowing allocates memory pages in the remote process by VirtualAllocEx, then writes the payload there. It gives one undesirable effect: the access rights (MEM_PRIVATE) were different than in the executable that is normally loaded (MEM_IMAGE).

Example of a payload loaded using Process Hollowing:

The major obstacle in loading the payload as an image is that, to do so, it has to be first dropped on the disk. Of course we cannot do this, because once dropped, it would easily be picked by an antivirus.

Process Doppelgänging on the other hand provides a solution: invisible transacted files, where the payload can be safely dropped without being noticed. This technique assumes that the transacted file will be used to create a section (MEM_IMAGE), and then this section will become a base of the new process (using NtCreateProcessEx).

Example of a payload loaded using Process Doppelgänging:

This solution works well, but requires that all the process parameters have to be also loaded manually: first creating them by RtlCreateProcessParametersEx and then setting them into the remote PEB. It was making it difficult to run a 32-bit process on 64-bit system, because in case of WoW64 processes, there are 2 PEBs to be filled.

Those problems of Process Doppelgänging can be solved easily if we create the process just like Process Hollowing does it. Rather than using low-level API, which was the only way to create a new process out of a section, the authors created a process out of the legitimate file, using a documented API from Kernel32. Yet, the section carrying the payload, loaded with proper access rights (MEM_IMAGE), can be added later, and the execution can get redirected to it.

Second stage loader

The next layer (8d58c731f61afe74e9f450cc1c7987be) is not the core yet, but the next stage of the loader. It imports only one DLL, Kernel32.

Its only role is to load the final payload. At this stage, we can hardly find something innovative. The Osiris core is unpacked piece by piece and manually loaded along with its dependencies into a newly-allocated memory area within the loader process.

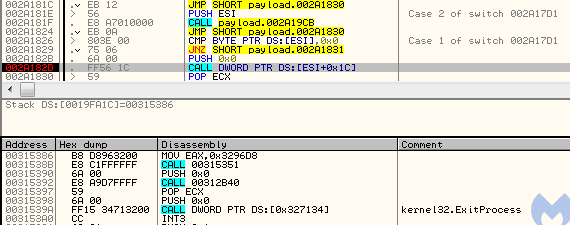

After this self-injection, the loader jumps into the payload’s entry point:

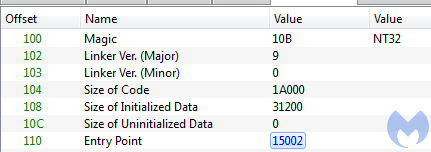

The interesting thing is that the application’s entry point is different than the entry point saved in the header. So, if we dump the payload and try to run it interdependently, we will not get the same code executed. This is an interesting technique used to misguide researchers.

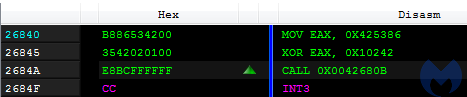

This is the entry point that was set in the headers is at RVA 0x26840:

The call leads to a function that makes the application go in an infinite sleep loop:

The real entry point, from which the execution of the malware should start, is at 0x25386, and it is known only to the loader.

The second stage versus Kronos loader

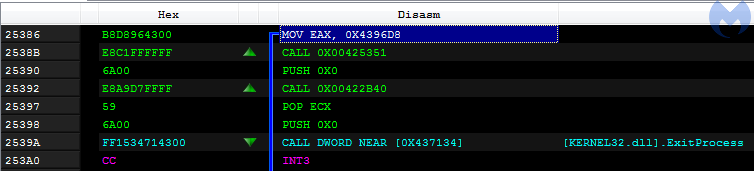

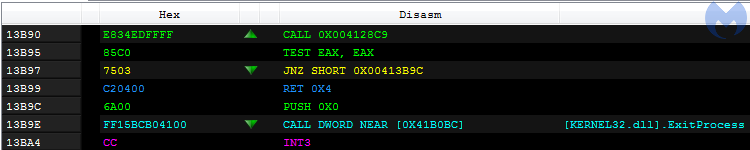

A similar trick using a hidden entry point was used by the original Kronos (2a550956263a22991c34f076f3160b49). In Kronos’ case, the final payload is injected into svchost. The execution is redirected to the core by patching the entry point in svchost:

In this case, the entry point within the payload is at RVA 0x13B90, while the entry point saved in the payload’s header (d8425578fc2d84513f1f22d3d518e3c3) is at 0x15002.

The code at the real Kronos entry point displays similarities with the analogical point in Osiris. Yet, we can see they are not identical:

A precision implementation

The first stage loader is strongly inspired by Process Dopplegänging and is implemented in a clean and professional way. The author adopted elements from a relatively new technique and made the best out of it by composing it with other known tricks. The precision used here reminds us of the code used in the original Kronos. However, we can’t be sure if the first layer is written by the same author as the core bot. Malware distributors often use third-party crypters to pack their malware. The second stage is more tightly coupled with the payload, and here we can say with more confidence that this layer was prepared along with the core.

Malwarebytes can protect against this threat early on by breaking its distribution chains that includes malicious documents sent in spam campaigns and drive-by downloads, thanks to our anti-exploit module. Additionally, our anti-malware engine detects both the dropper and Osiris core.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Stage 1 (original sample)

e7d3181ef643d77bb33fe328d1ea58f512b4f27c8e6ed71935a2e7548f2facc0

Stage 2 (second stage loader)

40288538ec1b749734cb58f95649bd37509281270225a87597925f606c013f3a

Osiris (core bot)

d98a9c5b4b655c6d888ab4cf82db276d9132b09934a58491c642edf1662e831e